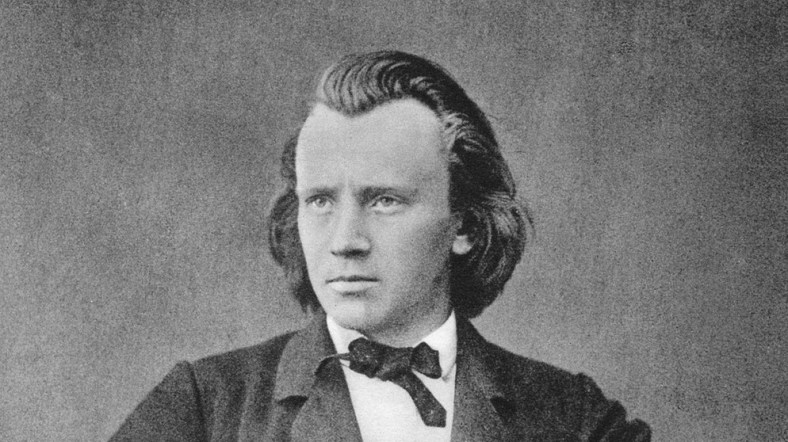

Dopo diverso tempo, riprendo in mano il filo della serie dei miei post di interpretazione liederistica comparata che sono sempre tra i più visitati del mio sito. Questa nuova puntata voglio dedicarla a un Lied che io considero un’ autentica perla nella produzione di Johannes Brahms. Si tratta di “Treue Liebe”, primo brano della raccolta Sechs Gesänge für eine Singstimme und Klavier op. 7, composta fra il 1851 e il 1853 e pubblicata l’ anno seguente. Il testo del Lied è di Eduard Ferrand, pseudonimo di B. Eduard Schulz (1813-1842), autore che pubblicò la maggior parte dei suoi lavori sotto il nome di Tybald e fu tra i fondatori del Vereins der jüngeren Berliner Dichter. Ecco il testo, seguito dalla mia traduzione.

Ein Mägdlein saß am Meerestrand

Und blickte voll Sehnsucht ins Weite.

»Wo bleibst du, mein Liebster, Wo weilst du so lang?

Nicht ruhen läßt mich des Herzens Drang.

Ach, kämst du, mein Liebster, doch heute!«Der Abend nahte, die Sonne sank

Am Saum des Himmels darnieder.

»So trägt dich die Welle mir nimmer zurück?

Vergebens späht in die Ferne mein Blick.

Wo find’ ich, mein Liebster, dich wieder,Die Wasser umspielten ihr schmeichelnd den Fuß,

Wie Träume von seligen Stunden;

Es zog sie zur Tiefe mit stiller Gewalt:

Nie stand mehr am Ufer die holde Gestalt,

Sie hat den Geliebten gefunden!

La mia versione italiana:

Una giovane sedeva sulla spiaggia del mare

e guardava piena di malinconia lontano.

“Dove sei, amor mio? Dove ti trattieni così a lungo?

La pena del mio cuore non mi lascia riposo.

Ah se solo tu tornassi oggi, mio amato!”venne la sera, il sole dispariva

in basso, all’ orlo dell’ orizzonte.

“Così le onde non ti riportano a me?

Inutilmente il mio sguardo cerca lontano.

Dove ti ritroverò, amore?”L’ acqua le sfiorava carezzevolmente i piedi,

come un sogno di ore beate;

la trasse al profondo con forza silenziosa:

la bella figura non stava più sulla riva,

aveva ritrovato il suo amato!”

Iniziamo la serie dei contributi critici con questa breve analisi, tratta dal sito del Leeds Lieder Festival.

Despite the beauty of Brahms’ music, the subject of the poem is actually rather depressing. A girl waits by the edge of the sea for her boyfriend who does not arrive; as evening falls, she realises she may never see him again; the water laps at her feet and her longing to be reunited with her drowned lover overwhelms her; she is drawn irresistibly into the water and joins him in death.

Brahms was born in Hamburg, in North Germany, and was therefore close to the sea. He would have been very aware of the dangers which faced sailors and also of the many German legends about the dangerous lure of water. Here, however, the theme is not ‘death by water’, but the power of true love, which unites two young people even in death. Despite the tragedy, the girl is an heroic figure, who demonstrates absolute faithfulness to her lover.

The opening of the accompaniment clearly suggests the lapping of the waves at the girl’s feet, but the same pattern of notes soon comes to represent the girl’s anxiety as she starts to fear the worst. This double use of a musical pattern for something concrete (the waves) and something emotional (fear) is an important feature of Romantic song.

After two identical verses, the third verse opens with a more excited piano figure. The replacement of the initial semiquavers by semiquaver triplets in rising phrases suggests extreme emotional turmoil. The girl is by now almost delirious with anxiety and realises what has happened. At the moment of drowning, where she is lured irresistibly into the water (‘es zog sie zur Tiefe …’ ‘those silent deep waters they draw her below’) the music is almost overwhelming, just as the water overwhelms the girl. The music calms down in the short final section and the song ends as it began, with the suggestion of gently lapping waves – which provides a neat frame to the song.

Di seguito, una disamina più dettagliata, proveniente dal sito Brahms Listening Guides.

1. Treue Liebe (True Love). Text by Eduard Ferrand. Andante con espressione. Strophic form with varied third verse. F-SHARP MINOR, 6/8 time. (Middle/low key E minor).

[m. 1]–Stanza 1, lines 1-2. The piano begins a quiet undulation depicting the waves on the shore. The flowing motion is passed between the left and right hands with overlap. After a measure, the voice enters on the upbeat with its gently rocking melody, reaching up and descending at the end of the first line. The left hand now takes longer breaks instead of overlapping with the right. On the second line the voice rises and swells to a high note, making a very brief harmonic detour to G minor and D major. At the high note on “Weite,” the piano rises and slows in an arpeggio before the voice drops down

[m. 6]–Stanza 1, lines 3-5. The piano’s sliding upward motion leads to the third line. The music is the same as the first line, but the piano is set an octave higher with the left hand reiterating the “dominant” note C-sharp. Long-short rhythms on repeated notes are used to accommodate extra syllables. The fourth line is set to a new and urgent surging line, doubled by the piano left hand. The right hand moves to upward arching arpeggios on unstable “diminished seventh” harmonies. The first statement of the fifth line is a step higher than the fourth and ends with a strong motion toward B minor.

[m. 12]–The voice leaps up to repeat the last line, which begins with a surge to forte in B minor. The left hand continues to double the notes of the voice while the right now incorporates wider leaps and rising octaves in its steady, constant motion. The voice moves down as the harmony moves back home to F-sharp minor. At the last word “heute,” the singer soars up in a poignant “tritone.” Under this, the piano sweeps up and down in an extended and colorful motion to the cadence, the voice settling on the expectant “dominant” note. In the bridge measure, the piano continues down, alternating lower and upper notes.

[m. 1]–Stanza 2, lines 1-2. Strophic repetition from Stanza 1 with a “split” repeated note on “nahte” and a “joined” note on “Saum.”

[m. 6]–Stanza 2, lines 3-5. Strophic repetition from Stanza 1 at 0:14 with a “split” repeated note on “Ferne” in line 4. The word “Liebster” in line 5 arrives at the same point as in the first stanza.

1:08 [m. 12]–Climactic repetition of the last line as at 0:30 with the “tritone” on “wieder.”

[m. 15]–Stanza 3, lines 1-2. Though marked dolce, the music is more agitated. The piano surges up in arpeggios, using triplet rhythm for the first time. At the top of each arpeggio, there is a “sighing” descent to the “dominant” note in straight rhythm in both hands. The first vocal line is like those in the first two stanzas, but with the new accompaniment. As the line comes to an end, the “sighing” descents gradually move upward. The second vocal line is changed, reaching higher and using repeated notes instead of a rising direction, and building strongly in volume. The harmony also avoids the harmonic detour, staying close to the home key. As the line ends, the “sigh” figures take over, reaching high and plunging down.

[m. 20]–Stanza 3, line 3. This is the crux and climax of the song. The voice stays on a repeated note, then leaps up to a longer one (D) on “stiller.” Under this, the piano plays a very colorful triplet arpeggio on an “augmented” chord and moves strongly to D, now D minor, on “Tiefe.” As the voice leaps up to “stiller,” another colorful harmony is heard in an arpeggio on E-flat. The voice follows this, moving up, then down, before settling again on the long-held D. The piano arpeggios, still in triplets, now become highly decorative, establishing D minor in a rising line, then moving in right-hand waves as the left settles on a held drone. These waves slow, diminish and descend after the voice drops out in the second measure.

[m. 25]–Stanza 3, lines 4-5. The piano’s arpeggios cease, and the music returns to the home key (F-sharp minor). Block chords accompany the statement of line 4, which resembles the typical setting of lines 1 and 3 in the other stanzas. There is one more reference to D (major) on “holde.” On the last line, the voice expressively decorates the word “hat” with grace notes, then descends in a similar way as in the other two stanzas, but quietly and over block chords.

[m. 28]–There is still a “tritone” on the last word “gefunden,” but it is changed, now starting on the upbeat a half-step lower, and rising to the “dominant” note, which is held a full measure. The piano’s right hand begins to play high arching arpeggios under it. The voice rises a step, to where the “tritone” had landed in previous stanzas, holds that note a full measure, then quickly moves through the “dominant” note and leaps down to the keynote F-sharp, holding it for two measures as the right-hand arpeggios slow, descend, and diminish over a low hollow left-hand harmony. These continue for another measure.

[m. 33]–The piano continues its postlude, returning to the patterns from the opening, an octave lower than before. After two very quiet ppp measures of these, the left hand plays three softly thumping reiterations of a low bass octave, the last one held.

END OF SONG [36 mm.]

Passiamo adesso agli ascolti. La prima versione che ho scelto è quella di Ria Ginster (1898-1985), cantante nativa di Frankfurt che negli anni Trenta e Quaranta fu considerata fra le più eminenti liederiste della sua epoca. La sua carriera fu quasi esclusivamente dedicata al repertorio concertistico, nel quale lavorò con i massimi direttori del tempo tra cui Bruno Walter, Otto Klemperer, Wilhelm Furtwängler col quale cantò la Nona di Beethoven ai Salzburger Festspiele 1937 e il giovane Herbert von Karajan che la diresse nel Deutsches Requiem di Brahms e nelle Jahreszeiten di Haydn quando era Generalmusikdirektor ad Aachen. La sua incisione risale alla fine degli anni Trenta, al pianoforte è Paul Baumgartner.

La voce è sorretta da una tecnica di ottima scuola e il senso del fraseggio e dello stile sono quelli di una liederista di autentica classe. Dal punto di vista interpretativo, molto efficace è il tono di doloroso, attonito stupore con cui la Ginster realizza gli ultimi due versi.

Veniamo adesso a Kirsten Flagstad (1895-1962) una delle massime interpreti wagneriane della storia e cantante fra le più grandi mai apparse sulla scena, che coltivò assiduamente anche il repertorio liederistico. La sua interpretazione proviene da un recital inciso per la DECCA nel 1956, con il pianista Edwin McArthur.

Se pensiamo che la Flagstad era sessantunenne all’ epoca di queste registrazioni e che aveva passato una vita a cantare un repertorio tra i più logoranti e faticosi, possiamo tranquillamente parlare di miracolo vocale. La voce è tonda, sonora, fermissima e il timbro è ancora quello degli anni d’ oro. La cantante norvegese interpreta il brano con un tono quasi epico, da antica leggenda narrata da una coetanea di Waltraute, ben evidenziato da un tempo abbastanza largo. Una grande esecuzione, senza alcun dubbio.

Proseguendo, ascolteremo tre cantanti della nostra epoca. La prima è il contralto inglese Carolyn Watkinson (1949), celebrata interprete del repertorio barocco nel quale ha lavorato assiduamente soprattutto con Chistopher Hogwood, insieme al quale ha realizzato incisioni discografiche ancor oggi di assoluto riferimento. L’ esecuzione è tratta da un recital del 1982, registrato alla Wigmore Hall.

Il timbro vocale scuro, denso e il fraseggio carico di mestizia sono i mezzi con cui la cantante britannica interpreta il brano con un tono di cupo pessimismo, decisamente molto appropriato. Ottima la pronuncia tedesca, anche nei minimi dettagli.

La quarta esecuzione è quella del soprano Juliane Banse (1969), nata a Tettland, vicino a Ravensburg nella zona del Bodensee, che ha studiato a München con la grande Brigitte Fassbaender e svolto una carriera di riguardo documentata anche da una ricca discografia in collaborazione con direttori come Claudio Abbado, Pierre Boulez, Giuseppe Sinopoli, Manfred Honeck e Simon Rattle. La Banse è considerata una tra le liederiste più autorevoli della nostra epoca e vale la pena di ascoltare la sua interpretazione, incisa nel 1999 nell’ ambito di un’ integrale delle musiche vocali di Brahms.

Il fraseggio ispirato e la delicatezza della pronuncia sono quella dell’ interprete di gran classe e tutta l’ esecuzione si caratterizza per il tono di morbida, crepuscolare malinconia perfettamente adatto al carattere del pezzo.

Come ultimo ascolro, propongo una cantante della giovane generazione. Si tratta di Nikola Hillebrand (1993), nativa del Ruhrgebiet, considerata una tra le nuove voci tedesche più promettenti del momento. Nata a Recklinghausen ma cresciuta a München dove ha iniziato a studiare il canto quanto frequentava ancora il Gymnasium, a soli ventidue anni, prima ancora di finire gli studi, ha debuttato al Glyndebourne Festival e un anno dopo è stata ingaggiata dal Nationaltheater Mannheim dove ha interpretato una quindicina di ruoli. Nel 2018 si è fatta conoscere a livello nazionale per la sua interpretazione di Adele nella Fledermaus alla Semperoper Dresden, trasmessa in diretta dalla ZDF il 31 dicembre come Silvesterkonzert. Dal 2020 fa parte dell’ ensemble del teatro sassone dove ha riscosso grandi successi come Königin der Nacht, Konstanze, Pamina, Musetta, Gretel, Annchen del Freischütz, Sophie e Gilda, affermandosi come uno tra gli elementi di punta della compagnia. Sin dagli anni della sua formazione Nikola Hillebrand ha praticato assiduamente il repertorio liederistico e la sua definitiva consacrazione è avvenuta nel 2019 con la vittoria all’ Heidelberger Wettbewerb. Il video proviene da un recital del 1° maggio 2022 tenuto a Leeds, nella Howard Assembly Room.

Ho ascoltato dal vivo Nikola Hillebrand pochi mesi fa in una Liederabend qui a Stuttgart ed ero rimasto colpito dal talento assolutamente fuori dal comune che questa giovane artista dimostra di possedere. Linea di canto immacolata, timbro prezioso, dizione scolpita e raffinata, fraseggio intenso e concentrato, capacità di giocare con le mezze tinte e le inflessioni sono tutte cose davvero molto notevoli, soprattutto in un’ artista appena trentenne e l’ esecuzione è ricca di fascino per il tono di spontanea comunicativa e la mestizia rassegnata degli accenti. Non una promessa ma già una splendida realtà, Nikola Hillebrand ha tutti i requisiti per affermarsi come una tra le migliori liederiste della giovane generazione.

Chiudiamo qui, sperando che abbiate apprezzato questa serie di ascolti. Nel 2024 avremo ancora l’ occasione per riparlare di Lieder.

Scopri di più da mozart2006

Abbonati per ricevere gli ultimi articoli inviati alla tua e-mail.

Excelente post y excelentes cantantes.

Muchas gracias por descubrirme este tesoro. Solamente conocía a Flagstad y lo que es peor todavía, tampoco conocía este fabuloso Lied de Brahms.

Feliz 2024, esperando mas posts de Lied

"Mi piace"Piace a 1 persona

Muchas gracias por estas amables palabras de agradecimiento

"Mi piace""Mi piace"